Effects of feeding polyclonal antibody preparation on feedlot performance, feeding behavior, carcass characteristics, rumenitis, and blood gas profile

of Brangus and Nellore yearling bulls

ABSTRAcT: The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of replacing monensin (MON) with a spray-dried multivalent polyclonal antibody preparation (PAP) against several ruminal microorganisms on feedlot performance, carcass characteristics, feeding behavior, blood gas profile, and the rumenitis incidence of Brangus and Nellore yearling bulls. The study was designed as a completely randomized design with a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement, replicated 6 times (4 bulls per pen and a total of 24 pens), in which bulls (n = 48) of each biotype were fed diets containing either MONfedat300mg/dorPAPfedat3g/d.Nosignificant feed additive main effects were observed for ADG (P = 0.27), G:F (P = 0.28), HCW (P = 0.99), or dressing percentage (P = 0.80). However, bulls receiving PAP had greater DMI (P = 0.02) and larger (P = 0.02) final LM area as well as greater (P < 0.01) blood concentrations of bicarbonate and base excess in the extracellular fluid than bulls receiving MON. Brangus bulls had greater (P < 0.01) ADG and DMI expressed in kilograms, final BW, heavier HCW, and larger initial and final LM area than Nellore bulls. However, Nellore bulls had greater daily DMI fluctuation (P < 0.01), expressed as a percentage, and greater incidence of rumenitis (P = 0.05) than Brangus bulls.

In addition, Brangus bulls had greater (P < 0.01) DMI per meal and also presented lower (P < 0.01) DM and NDF rumination rates when compared with Nellore bulls. Significant interactions (P < 0.05) between biotype and feed additive were observed for SFA, unsaturated fatty acids (UFA), MUFA, and PUFA concentrations in adipose tissues. When Nellore bulls were fed PAP, fat had greater (P < 0.05) SFA and PUFA contents but less (P < 0.01) UFA and MUFA than Nellore bulls receiv- ing MON. For Brangus bulls, MON led to greater (P < 0.05) SFA and PUFA and less (P < 0.05) UFA and MUFA than Brangus bulls fed PAP. Feeding a spray-dried PAP led to similar feedlot performance compared with that when feeding MON. Spray-dried PAP might provide a new technology alternative to ionophores.

Download the full PDF here - Effects of feeding polyclonal antibody preparation on feedlot performance, feeding behavior, carcass characteristics, rumenitis, and blood gas profile

Discussion

Feed Additives

Bulls receiving a spray-dried PAP had feedlot perfor- mance that was not different from bulls receiving MON when fed high-concentrate diets. However, LM area dai- ly gain by bulls receiving PAP during the growing period (Fig. 1) was greater than for those fed MON. Considering that 48% of PAP was active against proteolytic bacte- ria Clostridium sticklandii (ATCC 12662), Clostridium aminophilum (ATCC 49906), and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius (ATCC 49031), rumen proteolysis may have been reduced when PAP was fed, which would have in- creased RUP outflow to the small intestine. An increase in supply of postruminal protein during growing, when the RUP requirement is greatest (NRC, 2000), might ex- plain this response. This could explain the larger final LM area of bulls fed PAP and, conversely, the greater 12th- rib fat daily gain of bulls receiving MON (Table 2). Bulls fed MON also consumed less DM per meal and spent less time eating per meal, which may have collaborated to increase the number of meals per day in Nellore bulls.

The effect of MON on reducing DMI and meal length in cattle fed high-concentrate diets previously has been reported (Galyean et al., 1992; Erickson et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2014); but, with respect to DMI fluctuations, Pereira et al. (2015) did not observe a significant effect when in- creasing dose of MON, from 0 to 36 mg/kg, which is in agreement with this study. Pacheco et al. (2012) reported that feedlot performance of bulls was similar for those fed MON or a liquid PAP. Also, DiLorenzo et al. (2008) and Pacheco et al. (2012) reported that dressing percent- age was decreased when a liquid PAP was fed, but no feed additive effects on either HCW or dressing percent- age was detected in this study. Dressing percentage was less in this study when compared with trials conducted in United States, because Brazilian packing plants do not consider kidney and pelvic fat as carcass components and also require less back fat on the carcasses.

Regarding the blood gas profile, bulls receiving PAP had greater blood buffering capacity than those bulls fed MON, due to increased blood concentrations of HCO3, TCO2, BEB, and BEECF. Owens et al. (1998) reported that in cattle well adapted to high-concentrate diets, the risk of acidosis and consequent alterations in blood con- centration of bicarbonates and blood pH is low. The ab- sence of significant feed additive effect on blood pH may be attributed to the fact that bulls fed MON spent more time ruminating in the finishing period, which would have increased rumen-buffering capacity. However, all values related to the blood gas profile reported in this study fall in the range of normal blood status as reported by Carlson (1997). As a result, no significant feed addi- tive main effect was observed for rumenitis score. This indicates that alterations on rumen epithelium were in- consistent when MON was replaced with PAP. Pacheco et al. (2012) previously reported that the rumenitis score of bulls receiving a liquid PAP was less than for bulls receiving MON. Marino et al. (2011), in a study with 9 cannulated Holstein cows, reported that rumen pH at 4 h after feeding was not different for cows fed MON or a liquid PAP. The spray-dried PAP is a feed additive with greater specificity when compared with MON. This may explain the numerical reduction in the rumenitis scores and the greater blood buffering capacity shown by bulls fed PAP, which contains 26% of antibodies being active against Streptococcus bovis (ATCC 9809), which is a pri- mary lactic acid–producing bacteria of ruminants.

The greater concentration of PUFA in adipose tis- sues of Nellore bulls receiving PAP may be related to the greater blood HDL observed for bulls fed PAP in this study. The HDL are known to transport PUFA from small intestines into bloodstream (Bauchart, 1993; Della Donna et al., 2012), but the effect of spray-dried PAP on blood HDL concentration is still unclear. In general, MON reduces rumen biohydrogenation. Van Nevel and Demeyer (1995) reported that feeding MON inhibited hydrolysis of triacylglycerol and biohydrogenation of UFA in the rumen. As a result, feeding of MON will increase the concentrations of UFA in fat de- pots (Fellner et al., 1997). Also, the greater incidence of rumen lesions observed in this study for Nellore bulls may have caused an additional negative effect on ru- men biohydrogenation (Pacheco et al., 2012) in those animals. Jenkins et al. (2008) reported that rates of li-polysis were reduced when rumen fluid pH declined below 6.0. This could negatively impact the growth of structural carbohydrate bacteria, which are very pH sensitive and include some species that act during the biohydrogenation process (Sniffen et al., 1992). On the other hand, as Brangus bulls had lower rumenitis scores, no significant feed additive effect was observed for concentrations of myristic acid (14:0), palmitic acid (16:0), oleic acid (18:1), and MUFA:SFA ratio in adi- pose tissues of these animals; and besides that, feeding of MON to Brangus bulls led to greater concentrations of SFA and PUFA and lower concentrations of UFA and MUFA when compared with Nellore bulls fed MON.

Pacheco et al. (2012) indicated that liquid PAP did not affect the fatty acid profile of s.c. adipose tissue of bulls when compared with feeding of MON. However, in this study, feeding spray-dried PAP promoted minor changes on the fatty acid profile, such as increasing the PUFA concentrations of adipose tissues of Nellore bulls.

Biotypes

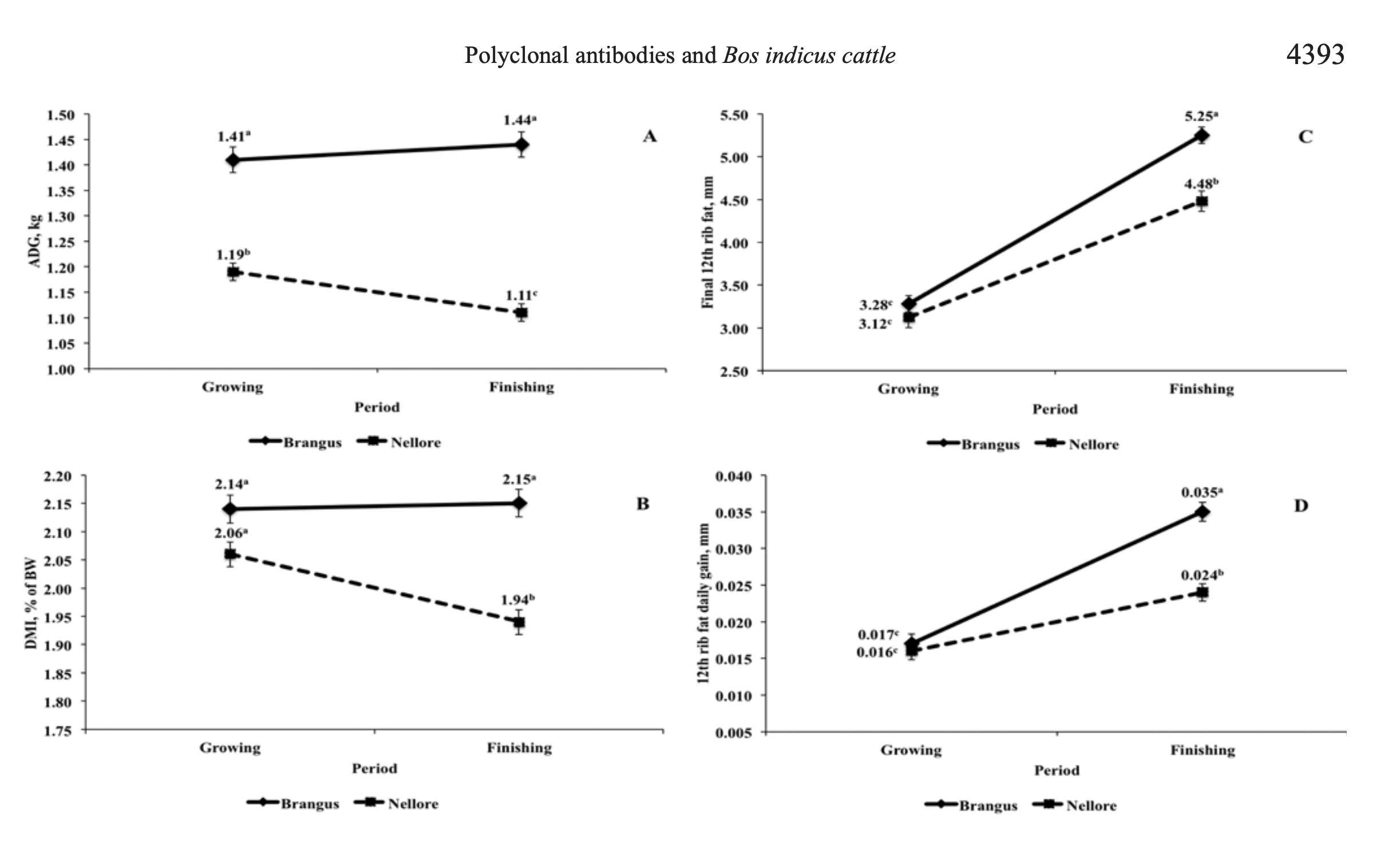

Compared with Nellore bulls, Brangus had supe- rior feedlot performance and carcass traits. These results may be explained partially by the greater incidence of rumenitis and greater DMI fluctuation of Nellore bulls. Brangus and Nellore bulls had similar DMIBW and 12th-rib fat daily gain in the growing period and a simi- lar G:F throughout the study. Brangus bulls had lower NDFCR in the finishing period than in the growing pe- riod; however, Nellore bulls took longer to consume a kilogram of NDF in the finishing period than in the growing period (Fig. 3) and also decreased DMIBW in this period (Fig. 2), which might be a result of greater ru-men acidification due to the 85% concentrate diet fed in this period that increased the incidence of rumenitis and increased DMI fluctuation (10.30 vs. 7.67%) for Nellore bulls throughout the study. Schwartzkopf-Genswein et al. (2004) reported that DMI fluctuations greater than 10% might negatively impact feedlot performance. Moreover, Pacheco et al. (2012) fed a finishing diet con- taining 85% concentrate to various Bos indicus biotype bulls, and they reported a greater incidence of rumen- itis for Nellore bulls than for Canchim (five-eighths Charolais and three-eighths Nellore) and a 3-way cross (one-half Angus, one-fourth Brangus, and one-fourth Nellore). When DMCR and NDFCR of Nellore bulls are impaired due to rumen acidification, blood buffer- ing capacity is reduced, and this could negatively im- pact blood concentrations of HCO3 and TCO2. These factors may explain the greater ADG and HCW as well as the greater 12th-rib fat gain in the finishing period of Brangus when compared with Nellore bulls.

When cattle progressed from the growing period to the finishing period, Brangus bulls had accelerated fat deposition; however, the G:F was not negatively altered when compared with Nellore bulls. Nellore bulls may have experienced more rumen acidifica- tion when switched to their finishing diet, and their decreased DMI and ADG could have delayed and reduced fat deposition, as biotype did not affect LM area daily gain. In addition, the improved feedlot per- formance of Brangus bulls relative to Nellore may be explained partially by genetic selection of British cattle for greater DMI potential. This could explain the greater DMI per meal by Brangus bulls and, conse- quently, their greater ADG and nutrient requirements for maintenance (NRC, 2000). Given the reduced DMI by Zebu cattle (6.62 kg for Nellore fed PAP, 6.36 kg for Nellore fed MON, 8.58 kg for Brangus fed PAP, and 8.13 kg for Brangus fed MON), which may be related to a combined effect of increased rumen acidi- fication and lower nutrient requirements for mainte- nance, their CP intake may limit growth performance (Millen et al., 2009), because ruminal escape of di-etary protein and efficiency of microbial protein syn- thesis are reduced when DMI is reduced, but this con- cept needs further study. Differences in mature BW of Brangus and Nellore bulls (Owens et al., 1995) might further explain differences in fat deposition among biotypes. A greater dressing percentage was expected for Nellore than for Brangus bulls because that was reported previously (Koch et al., 1982; Sherbeck et al., 1995; Pacheco et al., 2012). However, because Nellore bulls had lower DMI and 12th-rib fat daily gain dur- ing the finishing period, their carcasses had less 12th- rib fat than Brangus bulls (4.48 vs. 5.25 mm; Fig. 2), which would negatively impact dressing percentage.

With respect to fatty acid profile in adipose tis- sues, relevant variables were discussed in the previous section because of the interactions observed between biotype and feed additive. However, it is noteworthy to mention that the main effect of biotype with a great- er concentration of stearic acid (18:0) in the adipose tissues of Nellore bulls appears more responsible for changes in SFA, MUFA, and UFA concentrations than the main effect of biotype on increasing concentra- tions of myristoleic acid (14:1 cis-9), pentadecyclic acid (15:0), palmitoleic acid (16:1 trans-9), and CLA in Brangus bulls. Fatty acid Δ9 desaturase is respon- sible for converting SFA to MUFA in animal tissues, and its activity could be genetically controlled (Bartoň et al., 2010; Brugiapaglia et al., 2014). This could par- tially explain the differences in fatty acid profiles be- tween biotypes in this study. Feeding MON as well as the greater incidence of rumen lesions may have re- duced rumen biohydrogenation by Nellore bulls. The effect of biotype on stearic acid (18:0) may be related to increased de novo fatty acid synthesis; however, that theory needs further study.

Sites of Fat Deposition

Concentrations of SFA were greater in pelvic fat samples than in s.c. or intermuscular fat. Waldman et al. (1968) reported that the concentration of SFA in- creased from external to internal fat locations. Also, the higher concentrations of SFA and 18:0 suggest that rates of de novo fatty acid synthesis were greater in pelvic adipose tissue than in other fat depots (Kerth et al., 2015). On the other hand, the higher concen- trations of UFA, MUFA, and PUFA in s.c. adipose tissue may be related to its development from brown adipose tissue that is rich in MUFA (Chen et al., 2007). Differences in the fatty acid profiles observed from different fat depots in this study are not easily ex- plained. Further investigation is needed to determine the factors responsible for the differences in fatty acid profile among various adipose sites.

Conclusions

Brangus bulls had slightly faster and more efficient gains than Nellore bulls when fed feedlot diets. Further research is needed to examine the sensitivity of Zebu cattle to high-concentrate diets and their greater inci- dence of rumenitis. The fatty acid profile was affected, in general, by the interaction of biotype and feed addi- tive, which deserves further research as well.

Feeding a spray-dried PAP led to feedlot perfor- mance of bulls similar to feeding MON. Feeding a spray-dried PAP may provide an alternative feed addi- tive with potential to replace ionophores.